Shoulder Injuries in Tennis Players

Shoulder Injuries in Tennis Players:

Tight shoulders, predicting injuries and everything in-between

Regardless of your level of play, you’re likely to experience injuries when completing repetitive load in positions that require high levels of stability and the shoulder in tennis players is a prime example of this.

Marcondes et al. 2017 report that injuries in tennis equate to approximately 22 injuries for every 1000 hours of playing time, with the shoulder accounting for the majority of these injuries. If we break down these shoulder injuries into specifics, the three most common injuries sustained are SLAP lesions, where the labrum (cartilaginous ring in the shoulder) is torn, multidirectional instability and posterior shoulder capsule tightness. In previous posts we have identified the warning signs of labrum injuries and instability deficiencies, however haven’t looked closely into the tightness or pain at the back of the shoulder and what that may mean for prevention or recovery.

To crack the code of preventing or identifying factors that may reduce the incidence of these injuries is where we need to focus. In clinic we will see these conditions when pain has already set in and patients will ask “What has caused this?”. Quite frankly these conditions if not sustained in an acute fashion have likely been a long term gradual onset and contributed to from repeated activity, poor shoulder blade function (Scapular Diskinesia) or positioning (Scapula Posture) (Chung & Lark, 2017)

Why is the back of my shoulder tight?

Firstly to answer this question the demands of what Tennis players go through have to be broken down, and the serve is the perfect place to start, accounting for 45% to 60% of all strokes in a single match. The serving motion, a grossly dynamic technique is made of five phases as seen in Figure 1. each requiring heavy load on the rotator cuff and the soft tissue structures supporting it such as its variety of ligaments that make up the supporting capsule (Chung et al. 2017).

Figure 1. Phases of the serving motion (Kibler et al. 2006)

The physical demands from the Late cocking, Acceleration and Follow-through phases all produce their own different physical adaptations in the athletes shoulder.

The Late cocking phase

The Late cocking phase requires end range external rotation of the Glenohumeral joint at around 90 degrees, with an increase in external rotation associated with a more powerful serve. The trade off to this is generally -

1. A higher chance of the humeral head or ball portion of the joint to move posteriorly in the joint and place pressure on the posterior labrum if the supporting muscles aren’t capable of providing support

2. A reduced internal rotation range of movement compared to the non-dominant side, causing what is referred to as GIRD or Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit, objectively classified by a reduction of 18 degrees (Marcones et al 2013, Chung et al. 2017)

Cools et al. 2015 reported adaptations to range of movement such as reduced internal rotation, total shoulder range of motion, along with reduced external rotation strength and poor scapula movement as pre-season predictive factors for shoulder injuries (Cools et al. 2015). In addition Marcondes et al. 2013 showed clinically significant association between reported posterior shoulder tightness, increased GIRD and External Rotation ROM with reported shoulder pain when comparing tennis athletes with and without shoulder pain.

In other overhead sports such as Baseball studies have shown that even a 5 degree difference in total ROM between your dominant and non-dominant shoulder can increase your risk of injury by up to 2.5 times the normal rate (Nutt et al. 2018)

Acceleration phase

Possibly the most important aspect of the Acceleration phase is what can be referred to as the Kinetic Chain, a concept describing the production of energy through a particular route in the body. In this instance producing energy from the knee’s, through the trunk, into the shoulder and on into the elbow (Chung et al. 2017)

If energy transfer in a single joint is not efficiently coordinated, subsequent joints can easily become overloaded. For example, a biomechanical study of the tennis serve found that the mechanical loads transmitted to the shoulder and elbow increased by 17% and 23% in the absence of proper knee flexion when attempting to produce a velocity similar to that of a serve performed with correct knee flexion (Chung et al. 2017).

Follow-through Phase

Once that ball has been hit, the athlete needs to prepare themselves for what’s about to likely come back at them, the body now enters the Follow-through Phase. It is imperative the rotator cuff at the back of the shoulder slow the arm and exhibit as much Eccentric control as possible to absorb the energy produced by the kinetic chain. Due to the natural constraints of the game of Tennis, this has to be achieved within a quick time frame so a shortened follow through cycle has to be adopted in comparison to baseball pitching or a volleyball serve (Marcones et al. 2013).

If the capacity of the rotator cuff muscles is too poor for the demand of the energy produced in acceleration then the posterior capsule and ligaments underneath the ball and socket will absorb the load creating what is referred to as micro-trauma. It is in this phase that Marcondes, 2013 reported micro-trauma to the posterior capsule in athletes with a reduced internal rotation ROM of their serving shoulder (Chung et al. 2017).

This reinforces the role of coaching, strength and conditioning and physiotherapy to be intertwined to be able to look at all aspects of the athlete and where changes can be made to prevent these forceful movements causing long lasting problems.

Predicting Shoulder Injuries or Pain with Scapular Diskinesia

Is my shoulder SICK?

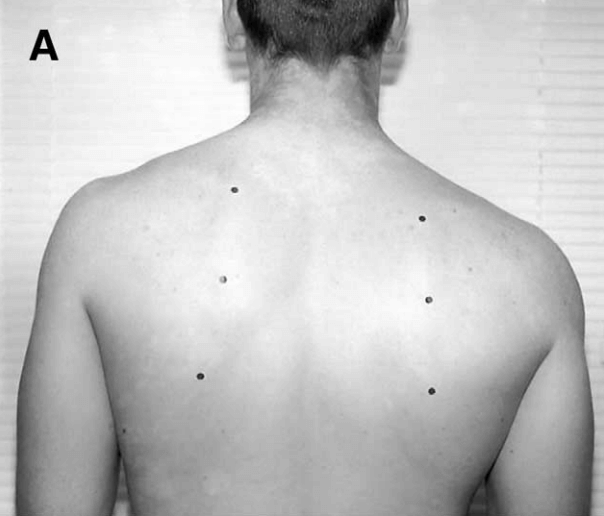

A popular term for a poor scapula position indicative of injuries in Tennis players and other overhead athletes specifically is SICK. The specifics of this condition are Scapular malposition, Inferior medial border prominence, Coracoid pain, and dysKinesis of scapular movement as seen on the right (Chung et al 2017).

Figure 2. SICK Scapula of Right Side Dominant Baseball Pitcher (Burkhart et al. 2003)

Scapular dyskinesis has been shown to contribute to rotator cuff pathology, as the rotator cuff’s scapula-humeral rhythm is disrupted by abnormal scapular range of motion. The rotator cuff injury we would most commonly see in both the amateur and professional athletes is a rotator cuff tendinopathy (Tendinitis) of which is most often associated with posterior internal impingement, which can cause fraying or tearing of the rotator cuff tendons with repetition.

In Tennis scapular protraction is produced due to a wind up effect as the arm, while continuing into forward flexion, internal rotation and horizontal adduction in follow through, pulls the scapula into internal rotation and anterior tilt. Recognising this and restoring the scapular into retraction should be a standard part of injury prevention strategies.

Not only do we look at single motion dyskinesia but just as importantly is dyskinesia resulting from fatigue was shown to be an important factor in producing errors of arm proprioception. As the rotator cuff muscles become tired and drift into the positions mentioned previously the sub acromial space where your tendons and bursae sit become narrowed, causing irritation in the point of the shoulder (Kibler et al. 2013).

Conclusion

Repetitive over head activity, like that of a Tennis serve will cause certain changes in the resting position and movement strategies of the dominant shoulder, that have been seen to predispose athletes to injury. These changes can be addressed, however significant assessment if required to be able to guide treatment, whether that be a stretching component to ease posterior capsule tightness, or an eccentric strengthening program to ease load in the follow-through phase. Not all shoulder injuries of the same muscle, tendon or ligament present the same so it is impossible to know what to give an athlete based on no assessment.